Taler ved utdelingen av Fritt Ords Pris 2022

Mandag 23. mai ble Fritt Ords Pris tildelt den russiske nettavisen Meduza i Den Norske Opera & Ballett i Oslo.

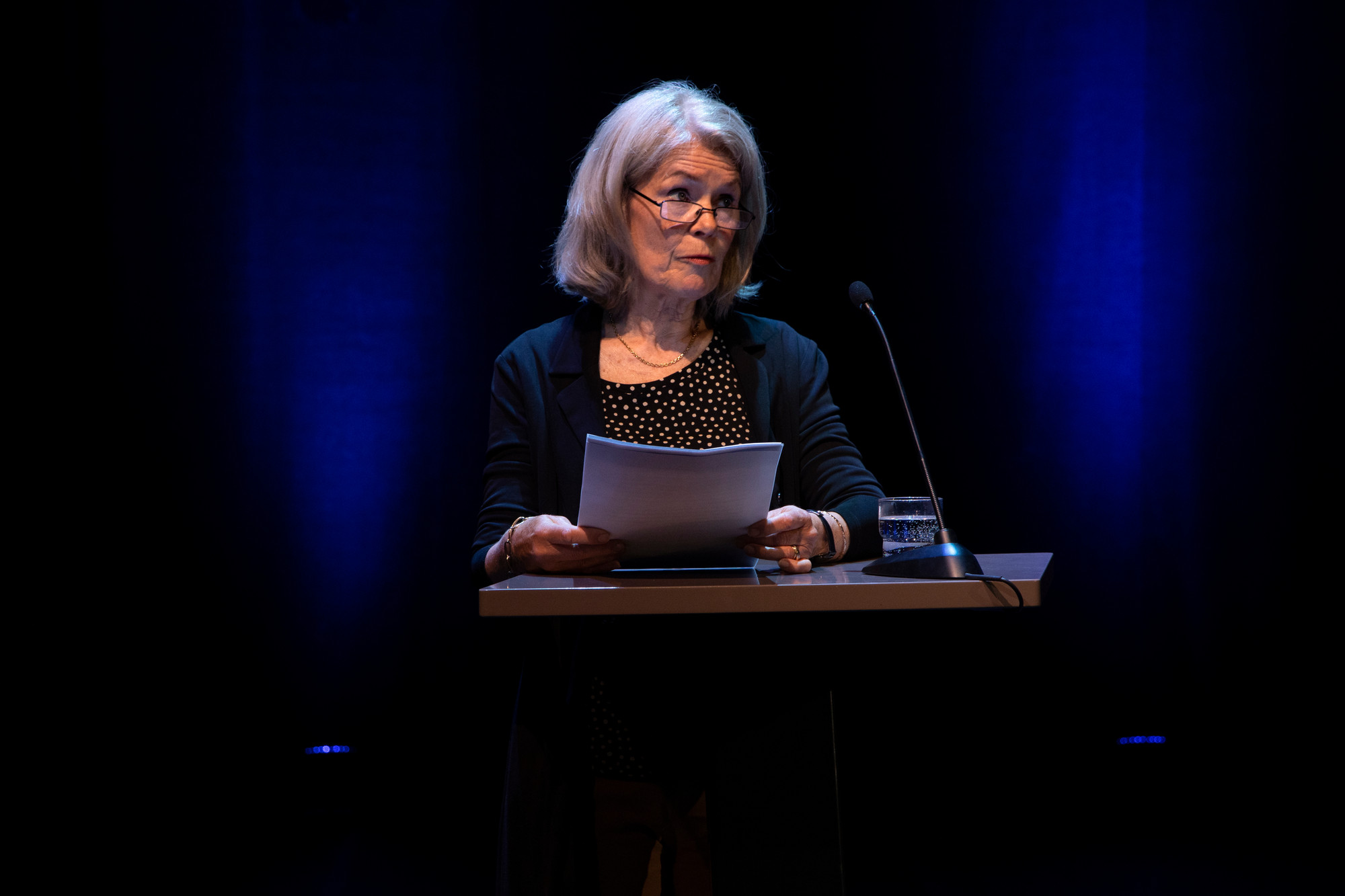

Prisen ble tildelt Meduza for modig, uavhengig og faktabasert journalistikk. Prisseremonien ble ledet av styreleder i Fritt Ord, Grete Brochmann. Talene ble holdt på engelsk.

Tale til prisvinnerne av Grete Brochmann, styreleder i Fritt Ord

Dear prize laureates, Meduza Publisher Galina Timchenko, Editor-in-chief Ivan Kolpakov, and dear guests,

Fritt Ord’s main distinction for 2022 goes to the media outlet Meduza for its courageous, independent and fact-based journalism, and for providing a trustworthy and high-quality source of news for Russians and the international community.

It is with a sense of sincerity and deep concern that we have invited all of you to Fritt Ord’s ceremony for our main award for 2022. This year’s prize has materialized in an extraordinary context. A brutal war has been taking place in Europe since Russia instigated an unprovoked full-scale invasion of its neighboring country Ukraine. After three months, this war has first and foremost drastically changed the lives of countless Ukrainians. Thousands of civilians have been killed, millions have been left in grief and fear after losing their homes and being forced to flee. But the war has also changed international relations worldwide. All of us are facing a changed world order, and our sense of security and predictability has been thoroughly shaken.

As is usually the case in armed conflicts, an information war is being waged as well. Media control, censorship as well as disinformation, but also outright coercion and arrests are all aspects of the war conditions facing the press. Together with eradication of a whole litany of civil freedoms, public voices are being silenced and controlled.

This is of particular concern for us in Fritt Ord, as a freedom of expression foundation. Protecting and strengthening the courageous use of written and spoken words is central to our mandate. Accordingly, it is only natural that journalism has become one of the most central areas of our work.

Meduza has carved out a prominent place for itself at the heart of today’s exceptional war journalism in Europe.

On February 24th, an editorial in the Meduza newsletter stated clearly: “Last night, Vladimir Putin announced the start of a ’special military operation’ in the Donbas. [….] We believe in calling things what they are: Russia has begun a full-scale war against Ukraine”. “We have a duty to state loudly and clearly that this is not our war [….]. The invasion of Ukraine was started on behalf of Russian citizens but against our will. The shame that comes with it will be with us forever”.

Meduza was born out of censorship in 2014, when then Editor-in-chief Galina Timchenko was fired from the website lenta.ru – one of Russia’s most followed websites at the time. The whole editorial team walked out with her, moved to Riga in Latvia, and established the independent news service Meduza with Timchenko as their leader. Today, Meduza is one of the most influential and most cited sources of investigative and reliable news and feature journalism from and on Russia and the surrounding region.

The web site is open and accessible to everyone, combining updated news items day and night with longer in-depth feature articles. It provides analyses of the current situation, that is, the economy, daily life inside the war zones and international relations. The latest news from the Russian leadership is confronted and contradicted, making use of research and expertise that exists in and on Russia. The outlet also documents activities and notable events on the ground through high quality photo-journalism, thus adding weight and urgency to the accusations of war crimes in Ukraine.

The news outlet, published in both Russian and English, works with a network of journalists in a number of countries in the region, reporting home to Russia as well as to an international audience. It rejects any attempts to curtail the freedom to report truthfully about the conflict or any other subject. Meduza has become an essential voice for reliable, dependable and fact-based information on Russian issues and the war that is going on. Meduza has become a hub for journalism across Eastern Europe, representing high-quality investigative journalism under extraordinary circumstances.

According to Ivan Kolpakov, now editor-in-chief, “We launched Meduza in 2014 in Riga, the capital of Latvia. We decided to create a media outlet in exile. Because our editors prepared for the worst from the very beginning, eight years later this strategy has helped us survive the complete destruction of independent journalism in Russia — at least for the time being.”

The backdrop for the current situation is that the Kremlin has systematically tried to obliterate independent media in Russia in recent years. Journalists have been fined, charged with being “foreign agents”, threatened and intimidated. Despite these efforts to clamp down on freedom of expression, this independent Russian media outlet has nevertheless managed to build an international reputation for its open-source investigations.

However, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin introduced a de facto ban on independent reporting in Russia. On March 1 the state censorship entity, the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Communication, also known as Roskomnadzor, ordered Internet Service Providers inside Russia to block access to Meduza’s website.

Meduza and a handful of other outlets were accused of “disseminating information in violation of the law”. The law, of course, was adapted because the Kremlin wanted a monopoly on the distribution of information to the Russian people about anything of importance – particularly information that concerns the invasion of Ukraine, which the Federal Service made unlawful to describe as either an invasion or a war. According to Meduza, “Russian authorities have now imposed military censorship in all but name, eradicating the entire domestic press”. Journalists now risk 15 years of imprisonment for doing their jobs. Today, most international news outlets have evacuated their staff members from Moscow for safety reasons. Hundreds of Russian journalists have fled the country.

Meduza nevertheless manages to provide reliable information on Russian affairs from their location in Riga. They still have high-level sources in the Russian government, and their reputation and legitimacy among the Russian public are considerable.

Meduza was well prepared for censorship and the rapid deterioration of platform accessibility after the start of the war: It launched a mobile app and built up a vast audience on social media before the ban. Today, the digital platform is facilitated by advanced methods of circumventing Russian control by diversifying platform usage. The news outlet actively uses Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram and YouTube. Meduza has its own podcasts, newsletters, and English language versions. Users in Russia have access using the app, despite the ban, even without the need to use a VPN.

Galina Timchenko underlines that digital innovation is immensely important under the current circumstances in order to skirt the so-called “digital iron curtain”.

In 2020 – even before the Russian invasion – Meduza was one of the ten most cited internet sources in the Russian language. Now the news platform reaches an even larger audience around the world, and its readership inside Russia has tripled since the attack on Ukraine.

Under the logo “Banned in Russia, but here for you”, followers of Meduza’s different news sites have access to a rich flora of texts and videos, articles, commentaries, analyses, the latest news, features, interviews, sharp editorials, etc.

Headlines reveal a broad scope of coverage, and here are some examples; “We’re on the Titanic, and it’s just hit the iceberg”; “From ‘frozen’ conflict to full-scale invasion – How has eight years of war changed Ukraine’s Donbas?”; “Blindsided – Russia’s top officials were caught off guard by Putin’s war in Ukraine. Many of them want to resign – but can’t”; “The poorer ones are already starving – Russian troops have controlled Kherson for a week. Here’s what life is like there now”; “Russia is the world’s top sanctions target – There are now more sanctions against Russia than against Iran, Venezuela, Myanmar, and Cuba – combined”; and “Feeling around for something human. Why do Russians support the war against Ukraine?”

Journalist Shura Burtin spent weeks talking to Russian citizens about feelings and thoughts in the midst of the war. His text reveals how “fear and a sense of humiliation defeated Russia’s humanity”. He provides an analysis of ‘deep pessimism’ – as regards what he calls a ‘learned helplessness’,’ where people are ‘blocking off arguments.’

“But what can be imagined on the other side of this war?”, he asks. “Ordinary people are dying there – it’s hard to bomb them into liking us …”

The outlet also offers critical and nuanced analysis on the dynamics of public opinion, and on the possible effects of economic sanctions on the presidential approval rating. And, not least, on the poor reliability of opinion polls as such in times of war. “Fewer people agree to answer questions, everyone has become more aggressive.”

Reviewing the independent, digital news site now, three months after the invasion, we find a mixture of war reporting on the ground in Ukraine, analyses of the international situation and the stakeholders on different sides, and critical scrutiny of the flow of information as such.

As always, in times of war, control of information is essential for securing the ownership of the interpretation of reality.

Chaos and concealment are two crucial effects of warfare without reliable reporters, according to two journalists reporting for the Associated Press in Mariupol: Chaos occurs when people do not know what is happening, and it is easy to panic. Concealment is made easier without accountable witnesses. Without reporters, the occupiers can do more or less what they want: No pictures of damaged buildings and kids who die. This means that ‘being there’ is essential.

Thought control is part of the ecology of oppression. Psychologists have been occupied with how propaganda shapes peoples’ minds. “Propaganda atomizes people. Bonds begin to deteriorate even within families.” “Indifference is our main problem” today, Meduza reports from Russian society. Graham Greene once pondered on the same effect: “It has always been in the interest of the repressive state to poison the psychological wells, to encourage cat-calls and to restrict human sympathy.”

Censorship corrupts all walks of life, politics, journalism, art, and literature. In the midst of the devastation, free speech is also under fire. It becomes vitally important to communicate the complexities of the situation – beyond the black and white logic of war. The role of media is crucial from a political perspective, but also for deeply ethical reasons. An environment without freedom of the press and media credibility cannot cherish democracy and human dignity.

According to Meduza, on March 3, censorship might not seem like a serious crime today —"especially compared to the murder of Ukrainian civilians. But the destruction of Russia’s independent media was one of the things that made this war possible. If we’re going to have any chance of stopping this war, we need an independent press".

Fritt Ord has wanted to highlight the important bridging function Meduza plays between Russian society and the outside world, particularly after the Ground Zero of February 24th. It has been increasingly difficult to access reliable coverage of the real situation in Russia, economically, politically, and culturally. “Putin and his men are not from another planet”, as was dryly stated by a Russian scholar some time back. “It is essential to understand his rationale, and the reactions of the population.” On the other hand, the Russian population needs information channels to the West; they need to see the war through Ukrainian eyes, as Ivan Kolpakov formulates it. Under the current war regime, there is a high risk of isolation from alternative sources of information as well as from human connection. Both these factors have potential long-term consequences for Russian society. Opposition forces now have to endure the dread of being “a cancelled nation”.

Meduza is awarded the Fritt Ord Prize for its courageous, independent and fact-based journalism for Russians and an international audience. The news outlet has challenged Russian censorship for years, and is now banned, maintaining its position under extremely demanding circumstances.

We thank you for your crucial contribution to truth-seeking and to open communication in these times of war, oppression and closure.

Congratulations!

Tale ved Galina Timchenko, publisher av Meduza:

Dear all,

I want to thank you from the deep of my heart, I’m thrilled and honored.

I think every person in the world at least once in a lifetime imagines such an acceptance speech (maybe in the shower, or in front of the mirror). You know every time I watch the Oscar ceremony I think that it’s unfair to give the award to those greedy guys — producers. Because the film is all about the director and actors and cameraman. Now as a publisher of Meduza I am this bad guy receiving the prize. So my part of the speech will be very short and I will give the floor to journalism — editor in chief of Meduza Ivan Kolpakov.

Some time ago I presented at the awards ceremony for the photojournalists. I spoke about the war. Not this horrible war against Ukraine. The one I mentioned started 20 years ago. I mean the war against freedom of speech, free press, free will, and mind, started by the Kremlin. Unfortunately, the Russian regime won this war: tens of media were named ‘foreign agents’ (enemies of the state). Tens of media were blocked, silenced, and stopped broadcasting and publishing. Wartime censorship was imposed, new laws promised up to 15 years in prison for the truth about the Russian invasion, and even the word “a war” was prohibited.

Today I have to say that we’ve lost this battle. Every time I give an interview I am asked about fighting against the regime. Despite all odds I want to say: I don’t want to fight against, I will fight “for” — our readers, their hearts.

And It’s worth it: we receive hundreds of emails from Ukraine. Some of them break my heart, they wrote: just don’t give up! Just go on! We are reading Meduza from a bomb shelter.

For sure now we are at the darkest hour. But I want to quote one man who once said: “Victory is not final. Defeat is not failure. It’s all about the courage to continue.”

Tale ved Ivan Kolpakov, sjefredaktør i Meduza:

Dear ladies and gentlemen, dear colleagues!

It is an honor for me — and for both of us of course — to receive this very important and respectable award here, in Oslo. Norway is well known as one of the best places for doing journalism on our planet. The standards of Norwegian media are incredibly high. The level of understanding among the society that independent journalism is an absolute and unique value here, in Norway, is remarkable. For many people from problematic regions (let’s put it this way) the Norwegian press looks like something futuristic and unreachable.

So, once again, we are honored and truly proud to be here.

Regarding the freedom of speech, Russia is also an example. But it is something completely opposite to Norway. While Russia is obviously losing the war in Ukraine, it is winning the war against its own journalists within the country.

This war is an old one. It started soon after Putin became a president for the first — and unfortunately not the last — time. During 20 Putins’ years, the Russian state forced quality journalism to the periphery of the market. First, the authorities got full control over the television. Then, they replaced the owners and the managers of independent newspapers with loyal or incompetent people. Very often — both.

This process was over after the 24th of February 2022, when Putin send troops to Ukraine. Military censorship was established in Russia. As it is already well known, even the word ‘war’ is forbidden in the country. Not to mention ‘peace’ of course. The president’s administration has crafted the law about so-called ‘military fakes.’ Fair and independent journalism is illegal. Reporting the war in Ukraine or the anti-war movement can be a reason for a criminal case.

Many important publications stopped the operation. The others were blocked. All the organizations that had any recourses evacuated their staff outside the country. Thousands of journalists had to run away from Russia without any support — and without any hope regarding the future.

In the light of these circumstances, we think that we are lucky and privileged people. Meduza was launched 8 years ago in exile. Our headquarters is based in Riga. We decided to move abroad because we were shocked by the Crimea annexation and the war in Eastern Ukraine that was provoked by Vladimir Putin. Also, a huge part of Russian society supported the annexation, this phenomenon is known as the ‘Crimean majority’. And it was frustrating.

In 2014, we did not believe that the political situation in Russia has any potential for positive changes. We understood it from our own experience. Almost all the reporters and editors in our team have faced state pressure. It would be correct to say that we were forced to leave the country.

During all those years we were like this weird character in the Hollywood movie that stands in the center of Manhattan with the poster — and the words ‘Apocalypse is coming’ are written on his sign. That’s why later, in 2022, Meduza survived — because we knew that the apocalypse is coming. And we were prepared for it better than many others.

For example, Meduza, like dozens of other publications, was blocked by the Russian government during the invasion. However, we are still accessible in the country. Since we started our work we were already blocked twice — in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. So we could collect the experience of life after death. Our app contains more than three anti-blocking tools. And it works in Russia perfectly fine. More than one million people downloaded our app, and the majority of them did it after the invasion started.

The future of Russian journalism is obscured. We know from history that it’s very challenging for the journalists to report from exile — and remain relevant to their native readers. We need to work hard to maintain high standards of our work and keep in touch with people on the ground. Though the internet gives us a huge amount of information from Russia, we have to develop new forms of operations in the country, including closer collaboration with our supporters and guerrilla reporting. And we can’t stop the experiments for a single moment.

Dear colleagues! The situation in Russia and in Ukraine reminds us that independent journalism is a precious and fragile value. When the authorities and autocrats destroy or manipulate the media, they immediately paralyze the number of democratic institutes. Free elections, freedom of expression, active civil society — all of that simply cannot work without independent publications. Authorities act like that because only without free media they power becomes unlimited.

The threat is closer than many people used to think. Putin’s regime is an inspiration for many countries. As well as Putin himself is a role model for many populists on all continents. The current state of independent journalism is a matter of huge concern in such countries as Turkey, Serbia, Hungary, and many others.

We live in a time of anxiety. We have legal reasons to worry about the future of our profession. But also our time is the time of solidarity and support. Freedom of speech is an international value, and journalism itself is an international language. I have a feeling that more and more people all around the world understand it better than ever before.

Last year I was delighted when the Nobel committee decided to give Peace Prize to Filipino-American reporter Maria Ressa and my Russian colleague Dmitry Muratov, chief editor of prominent oppositional newspaper Novaya Gazeta. We think that it was a prize for all independent journalists in the world who work in unfavorable circumstances.

Another example that makes me happy as a journalist and media manager is the decision of the Pulitzer comity to award all Ukrainian journalists in 2022. For me, it is a beautiful example of support and solidarity. I welcome this decision as fair and clever. I think many of us, including myself, have a lot to learn from our Ukrainian colleagues. Their country was attacked by the aggressor, however, thousands of Ukrainian reporters and editors keep doing breakthrough journalism. The only work of Ukrainian photographers deserves Pulitzer.

Independent journalism is not a gift, it is an achievement that has to be protected. And even more than that. We have to fight for it. It is also remarkable that now any person on Earth can easily participate in this fight. You can support journalists from any place in the world including the sofa in your living room. You can participate in crowdfunding. Or spread the word about reporters who need urgent help.

In the end, I want to thank all the team of Meduza. Our reporters who work in Ukraine, and our authors in Russia. Our editors, designers, developers — in fact, a very small group of people. But they create the largest Russian independent media outlet. I am thinking of you right now, and I am proud of you. This award is for you.

Thank you!